“Sex and Relationship Education– Addressing Faith Communities Concerns” Conference

Faith Network for Manchester

7th November 2019

Keynote address

Good morning

Let me first of all offer my thanks to Faith Network for Manchester, and to Rabbi Warren Elf for the invitation to speak today.

The theme of today’s conference is Sex and Relationships Education- and I will get there but I would, first of all, like to establish the framework within which I think it is important that the discussion takes place. I am a person of faith, I have been a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for over thirty years and currently serve as a Bishop within that community. My beliefs and my faith are an integral part of who I am and the way that I view the world. I think it is important that no-one regardless of belief, worldview or identity should be asked to hide who they are.

Let me share an example of this from my own life. In applying for a PGCE, during my interview I was asked how my faith would affect me in the classroom. To contextualise I had spent 2 years on a proselytizing mission for my church prior to my undergraduate study, so my cv highlighted my religious commitment. The implication was that it would have a negative impact on my role as a teacher. I was very insistent that my religious beliefs and my persona or role of a teacher would be to use a Dawkinsesque term “non overlapping magisteria”- never the twain would meet. I was worried that, belonging to a missionary oriented aspect of Christianity, I would be accused of undue influence. I realize now my youthful naivety in trying to compartmentalise areas of my life. My faith, my beliefs, my view of God, human nature, who I am and the process and importance of learning are part of who I am, rather than bolt on and off accessories that I wear when it is convenient.

Although my faith as a disciple of Jesus Christ is central to my life and all of my choices and behaviours, I can say that after over twenty years into my career I do not, and never have, shared my personal beliefs with a high school class. I live my religion within the classroom but do not answer personal questions about my faith. If you were to ask my pupils what I have explicitly taught them about my faith during lessons they would struggle to know, but they might do better in listing the qualities that they believe a Latter-day Saint Christian has. I remember a group of university students once commenting that they were looking forward to visiting a local chapel because they would find out what Latter-day Saints believed. I was confused, and said that surely they knew what I believed. They said: “No, from you we have learned how Latter-day Saints live their lives, but not what they believe.” As an educator I quite liked this response.

I realised through that experience that we should all be allowed to be true to who we are and the values that we hold. That being said, the right to be who we are is coupled with an honesty and humility in dialogue, an openness to learning and a responsibility to strive to understand others and lift them. Apologies for beginning with a couple of personal experiences but if you would bear with me through one more I would appreciate it.

“We’re worried about Jimmy; we’re worried that he’s going to lose his faith.”

This was actually something that some members of my local church community said to my mum a few weeks after I had returned from my mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. What had precipitated this conversation? I was still attending Church, I was teaching my youth Sunday School class, I was still participating in every other aspect of my religious life. The concern? I was preparing to leave home to go to University; in and of itself this wasn’t problematic, though as a University Professor and a parent I can now see the concerns that some people have with the lifestyle that seems to be common among many students. The issue was that I was going to study Theology and Religious Studies at a University with an Anglican foundation. Much later I came across a book written by John Hull about how food metaphors could be used to illustrate the importance of learning about other faiths. He outlines a particular attitude that might be found within people of faith, and within wider faith communities:

“I am holy, the argument says, and you are holy but the ground between us is unholy

ground and we will contaminate each other through harmful mingling of blood if we meet” (Hull, 1991, p. 38).

The idea seemed to be that be coming into contact with ideas and beliefs from outside my faith tradition then my personal faith would be challenged and potentially eroded.

Is this how we see people who hold views that are different to ours? That somehow through allowing other people to express those views, or by associating with them our views will somehow be tainted? I assume it doesn’t take much effort to join the dots when we consider the furore over the implementation of the new guidelines for the teaching of sex and relationships education. I will return to this discussion, but let me explore the importance of a dialogue not based on this mistrust, or a dialogue that doesn’t automatically assume that our beliefs and way of life will be threatened by those who hold different views or live in a different way.

There are two pieces of art/sculpture that encapsulate the approach that I am going to suggest. Firstly, the Cathedral by Rodin.

As you look at this sculpture can I please ask that you try and recreate the position of the hands?

Most, if not all, of you will have begun the activity by trying to do it all yourself. At some point you will have realised either by experience or by observation that it is only possible as you work with someone else.

The second art installation is slightly more enigmatic. It is called ‘Holy Ground’ by Paul Hobbs.

Although he discusses its meaning at length on his website, I have interpreted it in my own way. It is a picture of the burning bush, around it are shoes from people around the world, taken off in an echo of when Moses removed his shoes in front of the bush because he was standing on Holy Ground. The shoes are emblematic to me of people in dialogue. There is a possibility that with both parties being firmly rooted in their own faith or worldview a third space opens between them where genuine dialogue can take place. Teece argues that rather than a place of harm, “it is the space between us that constitutes holy ground, holiness being discovered through encounter” (Teece, 1993: 8). The dialogue becomes “open” when the exchange of ideas is honest, and each party is open to learning rather than acceptance. Greggs has argued that:

By engaging with the religious other, the practitioner of inter-faith engagement is in dialogue with other religious traditions, but, by engaging in the activity of dialogue with the religious other, practitioners of any individual faith are also in dialogue with the particular tradition of their own faith. In this way the transformative nature of inter-faith dialogue can become reformative for the individual communities of those who engage in it (2010: 201).

For any person of any background this means that by engaging with others, and the thoughts that they have, they are open to the reformation of some of their practice or beliefs. As a crude example, engaging with a Muslim about the purpose and practice of fasting and listening to what that person feels and experiences, may enable me to evaluate their own attitude and motivations towards the law of the fast. Recognising that we can learn from others opens us to this type of transformative learning. Brueggemann’s discussion of dialogue in the Old Testament can be used to explore how dialogue can be transformative when the two parties engaged begin from unequal positions:

… [T]he defining category for faith in the Old Testament is dialogue, whereby all parties– including God– are engaged in a dialogic exchange that is potentially transformative for all parties… including God. This constitutes a conviction that God and God’s partners are engaged in mutual talk. That mutual talk may take a variety of forms. From God’s side, the talk may be promise and command. From the side of the partners, it may be praise and prayer. The Old Testament is an invitation to reimagine our life and faith as a dialogic transaction in which all parties are summoned to risk and change (2009: xii).

I love the idea that Brueggemann suggests that dialogue is an endeavour of risk and change. Engagement with others thus becomes a “dialogic transaction” whereby we may begin to change some of their understandings and behaviours. Inter-faith encounter may become transformative of our own belief and devotion. However, for a person rooted in a specific worldview it should always be remembered that there are parameters of orthodoxy that should be maintained.

Joseph Smith argued that engagement with other religions is about developing relationships, he felt that people should build one another up and “cease wrangling and contending with each other, and cultivate the principles of union and friendship in their midst” (Smith, J. 1938: 313). This also means that when we engage with others we should recognize the value and purpose of such dialogue. Gordon B. Hinckley suggested that in such encounters we should “Look for their strengths and virtues, and you will find strengths and virtues in your own life” (in Dew, 1996: 576). This will, in no small part, come from defining oneself as other− in asserting and defending unique and divergent beliefs with those held by others. However, it will also come in the encounter between people and religions.

It is possible to posit the existence of a dialogical space between us constitutes “holy ground”. This third space enables a place where adherents of two religions or worldviews meet to transform their understanding of one another, but also their understanding of themselves. The concept of a dialogical third space borrows heavily from the work of Bhabha (1994) but diverges from the resultant hybridity models that he suggests such spaces would create. Engagement with a third space as a place of “radical openness” (McMaster, 1999: 28) provides a perfect description of the type of space needed for dialogue to be successful. The way that this space can be “radical” and transformative at the same time is in utilizing areas of convergence and divergence.

What does this have to do with education and specifically sex and relationships education? In every area of life we are engaged in dialogue- the choice is whether we shy away from discussion perhaps because we are worried about our beliefs becoming diluted or tainted. Or, it is whether we embrace dialogue as a genuinely transformative opportunity.

If we were to believe every headline that is published we would perhaps think that what is being taught in schools is scary and inappropriate. According to news sources sex and relationships education:

- Promotes pornography (The Times-8 Oct 2019)

- Teaches Primary School children about masturbation (The Independent-30 Aug 2019)

Other views are suggesting that sex education might explore the how of homosexual sex in primary schools, and that abstinence is an archaic attitude. Most of the ‘clickbait’ headlines come from quotes from ‘religious groups’ that have participated in protests or have reacted to a perception rather than anything concrete.

If people read the guidelines surrounding sex education they will quickly realise that what is being taught, and what is suggested in the new guidelines are as far from the headlines as is possible. It is possible to suggest that we should allow people to speak for themselves rather than hearing about things second hand. The Guidelines (DfE, 2019) suggest:

The objective of sex and relationship education is to help and support young people through their physical, emotional and moral development (p. 3).

Pupils need also to be given accurate information and helped to develop skills to enable them to understand difference and respect themselves and others and for the purpose also of preventing and removing prejudice. Secondary pupils should learn to understand human sexuality, learn the reasons for delaying sexual activity and the benefits to be gained from such delay, and learn about obtaining appropriate advice on sexual health (p. 4).

Effective sex and relationship education does not encourage early sexual experimentation. It should teach young people to understand human sexuality and to respect themselves and others. It enables young people to mature, to build up their confidence and self-esteem and understand the reasons for delaying sexual activity. It builds up knowledge and skills which are particularly important today because of the many different and conflicting pressures on young people (p. 4).

Inappropriate images should not be used nor should explicit material not directly related to explanation. Schools should ensure that pupils are protected from teaching and materials which are inappropriate, having regard to the age and cultural background of the pupils concerned. Governors and head teachers should discuss with parents and take on board concerns raised, both on materials which are offered to schools and on sensitive material to be used in the classroom (p 8).

It will help young people to respect themselves and others, and understand difference. Within the context of talking about relationships, children should be taught about the nature of marriage and its importance for family life and for bringing up children. The Government recognises that there are strong and mutually supportive relationships outside marriage. Therefore, children should learn the significance of marriage and stable relationships as key building blocks of community and society. Teaching in this area needs to be sensitive so as not to stigmatise children on the basis of their home circumstances (p. 11).

It is up to schools to make sure that the needs of all pupils are met in their programmes. Young people, whatever their developing sexuality, need to feel that sex and relationship education is relevant to them and sensitive to their needs. The Secretary of State for Education and Employment is clear that teachers should be able to deal honestly and sensitively with sexual orientation, answer appropriate questions and offer support. There should be no direct promotion of sexual orientation (pp. 12-13).

I have chosen aspects of the guidelines that I think address some of the issues that seem to be headline grabbing, We need to be aware that news sites are looking for clicks, and while they may report opinions as opinions, the headlines may not always reflect that. As a person of faith I have absolutely no issues with the way that sex education is to be taught. What I appreciate is the opportunity I have as a parent to discuss all of these issues with my children. It opens up a third space- why do we believe as we do? If people hold different views what can I learn from them? Hiding away from these questions, or worse shouting them down will lead to walls of silence in our homes, and potentially our places of worship where children do not discuss such issues because there is no scope or opportunity for open discussion.

Is my faith in danger because my children will be taught that loving relationships can exist between people of the same gender? Obviously not, but my children’s faith may be if I fail to help them engage with the reality of life. I want my children to understand what healthy relationships are, and also their responsibility to understand others and support all people’s rights to be respected. Joseph Smith once taught:

The Saints can testify whether I am willing to lay down my life for my brethren. If it has been demonstrated that I have been willing to die for a Mormon, I am bold to declare before Heaven that I am just as ready to die in defending the rights of a Presbyterian, a Baptist, or a good man of any other denomination; for the same principle which would trample upon the rights of the Latter-day Saints would trample upon the rights of the Roman Catholics, or of any other denominations who may be unpopular and too weak to defend themselves (Smith, J. 1938: 313).

I would suggest that in today’s world this could be extended to include immigrants, Humanists, LGBTQ+, and many more. In 2007 I worked at a school in Manchester- as Director of Social Science we planned anti-homophobia training for staff prior to implementation and teaching the children. At the time I was a faith leader for Latter-day Saints across Manchester. After the training, one of the staff approached me, who was also a Latter-day Saint, and chastised me for teaching things antithetical to the Church. I asked him what about treating other people positively did he feel was opposed to the Church. He got so hung up on sexual activity that he lost sight of something that lies at the heart of all religion, and the heart of all relationships- to treat other people in the way that we would like to be treated:

Baha’i: Lay not on any soul a load that you would not wish to be laid upon you, and desire not for anyone the things you would not desire for yourself (Gleanings From the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh)

Buddhism: it is a very good deed to cast away greed and to cherish a mind of charity… One should get rid of a selfish mind and replace it with a mind that is earnest to help others. (The Teaching of the Buddha. Way of Practice II:9)

Christianity: In everything do to others as you would have them do to you. (Matthew 7:12)

Hinduism: This is the sum of duty; do nothing to others which would cause you pain if done to you.(Mahabharata 13:114)

Humanism: Trying to live according to the Golden Rule means trying to empathise with other people, including those who may be very different from us. Empathy is at the root of kindness, compassion, understanding and respect – qualities that we all appreciate being shown, whoever we are, whatever we think and wherever we come from. (Maria MacLachlan, Think Humanism)

Islam: No one of you is a believer until he desires for his brother that which he desires for himself. (An Nawawi, Forty Hadith 13)

Jainism: In happiness and suffering, in joy and grief, we should regard all creatures as we regard our own self (Lord Mahavira, 24th Tirthankara)

Judaism: For the Lord your G-d is G-d of gods, and Lord of lords, a great G-d, mighty, and awesome, who favours no person, and takes no bribe: he executes the judgement of the fatherless and the widow, and loves the stranger, giving him food and raiment. Love therefore the stranger, for you were strangers in the Land of Egypt. (Deuteronomy 10:17-21)

Sikhism: Do not harbour hatred against anyone. In each and every heart, God is contained. (Guru Arjan Devji, Guru Granth Sahib 259)

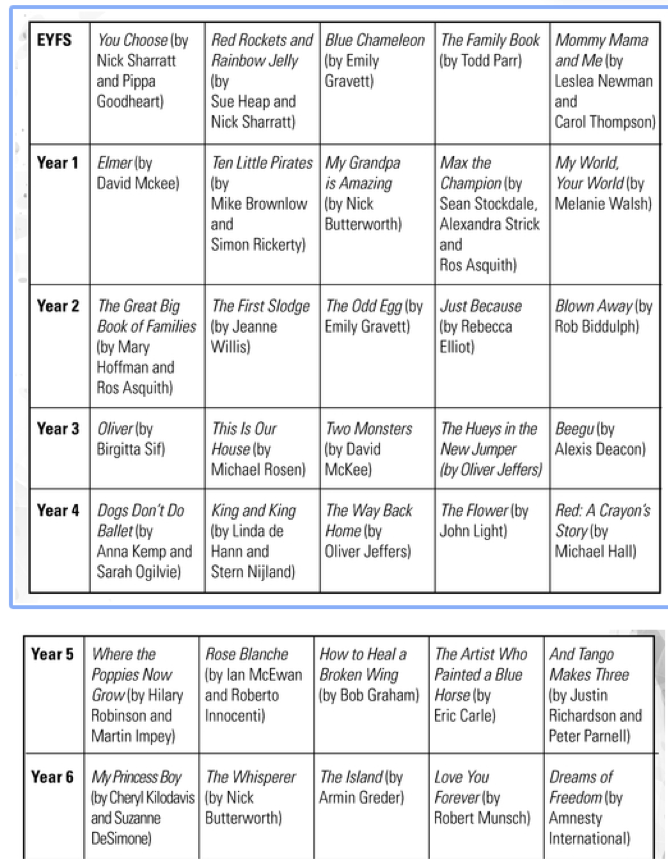

The No Outsiders approach receives negative publicity for its focus on homosexual couples. It is an approach and a resource, however, that focuses on the equality of all. If we look at books that are suggested for use as a part of the approach we quickly recognise it’s about inclusion and diversity rather than promoting a particular sexuality:

(Moffat, 2017, Table 7:1)

This is not indoctrination by the back door- this is a recognition that we are all different and that there are many different ways to be human.

It does not mean that very approach taken towards the teaching of Sex and Relationships Education is appropriate- teachers are fallible. That is why parents should involve themselves in the education of their children- both in the home and in the school.

In my recent book ‘Beyond the Big Six Religions’ I reflect on the power dynamic within society and within education:

The presence in our schools of some individuals with clear religious views should be seen as an opportunity to share our common understanding and respect for each other on our overlapping journeys. Such contributions can enrich school life, and help pupils feel as though their voices are important. Excluding pupils from inclusion or participation may make them feel isolated. McGarvey suggests that in such structures where people feel that their voices are not heard the desire to participate diminishes:

Enthusiasm to take part and be active in communities quickly dissipates when people realise the local democracy isn’t really designed with them in mind; that it’s designed primarily so that people from outside the community can retain control of it, over the heads of those who live there.

…Listening to and valuing every child as an individual is crucial. As such, if the RE classroom contains people from beyond the big six, it is crucial that they have a voice to explore and express their beliefs (2019, pp.7-8).

We need to help children feel as though all backgrounds and life experiences are valued so that they can recognise their value and place in society. The interplay between religion, worldviews and education is key. Parents and faith communities should see every aspect of their child’s education, including sex and relationship education as an opportunity for discussion and learning. We may not agree with everything, but that is not the point. If we hold on too tight, and shelter children too much from things that we disagree with then they will be ill prepared for life in the real world. Returning to the idea of dialogue as a transformational third space- we can see the benefits of engaging with Sex and Relationships Education as individuals, families and faith groups. I am not going to agree with everything that is taught but if I want my voice to be heard and understood I need to engage in the process and the provision of sex and relationship education for my children.