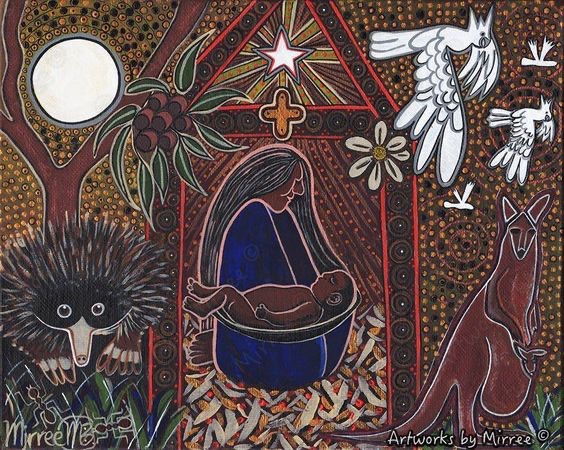

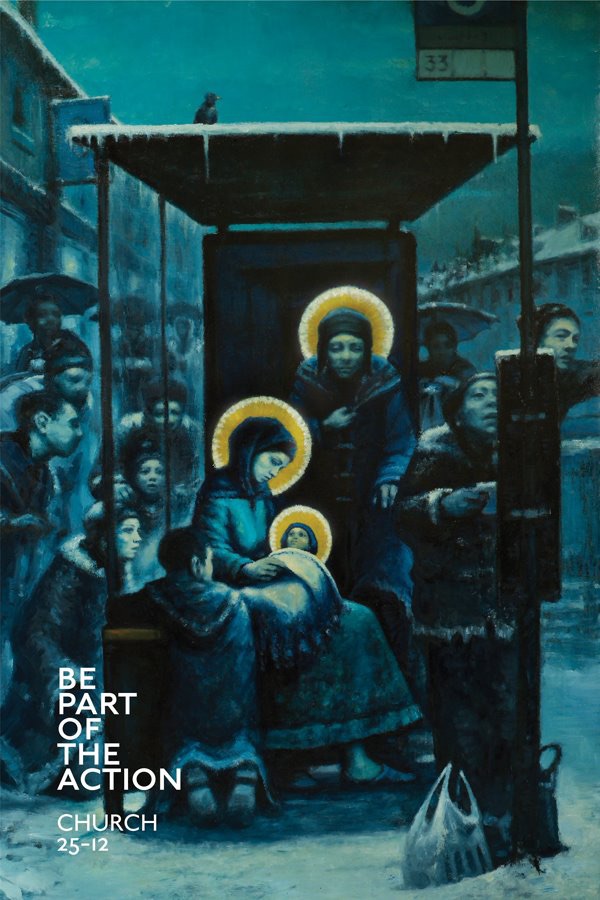

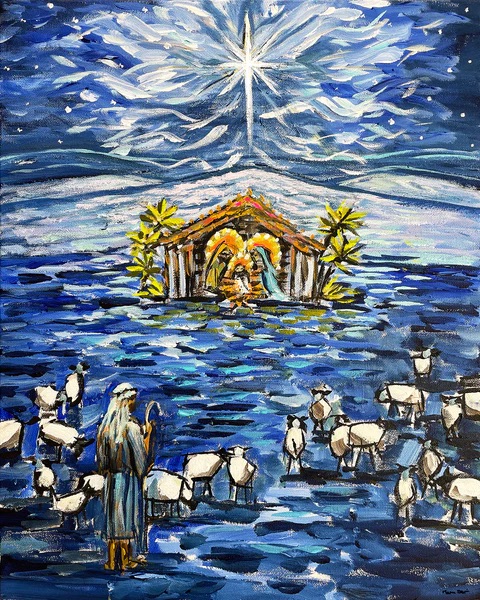

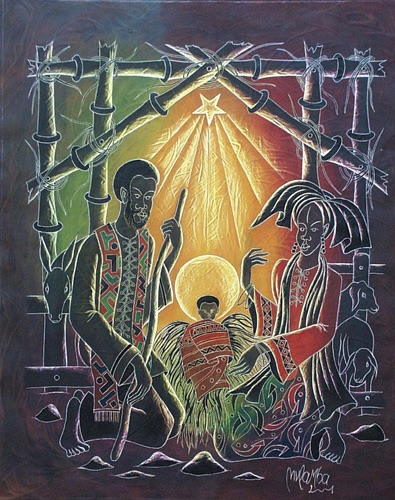

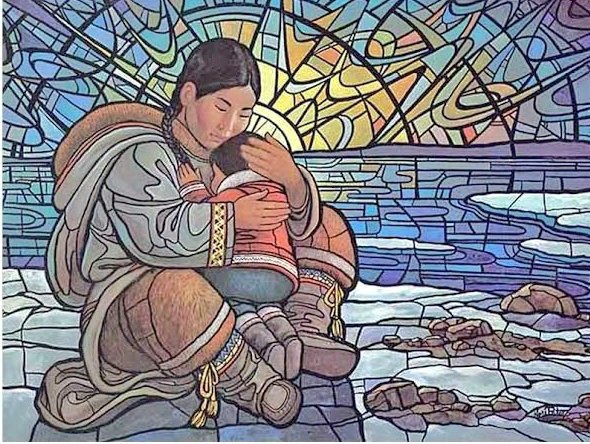

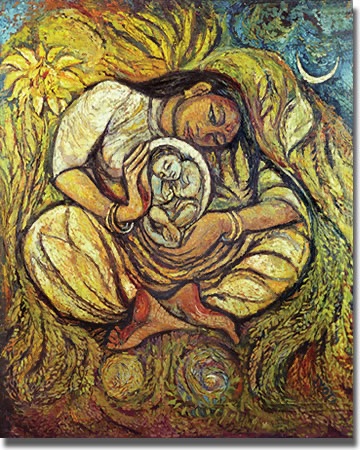

Over the period of Advent I have been sharing different images of the Nativity from around the world on Instagram and Facebook. I have been doing this as a Christian, and also as someone involved in Religious Education. The criteria for choosing the images have been subjective and usually surrounded what appealed to me as art. Underlying all of the choices, however, was to highlight how the nativity has been depicted from artists around the world. I have included art from England, Mexico, the USA, Ukraine, Palestine, China, Bulgaria, the Yukon, India, Australia, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to name but a few. These are diverse in both the country of origin, and also in the way the holy family are depicted.

(Update: I’ve repeated the exercise in 2024 and posted the artwork here)

(Update: I’ve repeated the exercise in 2025 and posted the artwork here)

This is purposeful. In my teaching I use a range of images of Christ that show him with different ethnicities. I encourage my students who are training to be teachers to continue this in their practice in the classroom. There may be some disequilibrium caused as children see images of a non-white Christ, but, for me, this is a positive aspect of children’s (and adults’) learning. We are challenging the norms that we have come to accept. The question I would like beginning to teachers to consider is why does an image of a Chinese Christ, or a black Saviour affect the sensibilities of some? Or maybe if it affects us, why?

The Anglican theologian Alister McGrath recently said: “The incarnation is a game changer. God comes to where we are to bring us to where he is.” And, where are we? We are in the mortal condition with our various characteristics of gender, race, and more. Therefore, when God comes to us where we are, he does not judge us on these bases, but He comes to us as the individual we are, with all of our characteristics. Therefore, for a person to encounter God where they are through art it may be through representations that they can recognise. For me, these artworks do not restrict who God is, nor do they distract from my worship of Him. Rather, they enable me to understand that God is the God of the whole world, and anything that can help us find Him is to be counted as good. In my own faith tradition there is a passage from scripture that suggests:

For behold, the Spirit of Christ is given to every man, that he may know good from evil; wherefore, I show unto you the way to judge; for every thing which inviteth to do good, and to persuade to believe in Christ, is sent forth by the power and gift of Christ; wherefore ye may know with a perfect knowledge it is of God (Moroni 7:16).

Further, Bruce R. McConkie reiterated that this extends to art:

The Spirit of Christ is the medium of intelligence that guides inventors, scientists, artists, composers, poets, authors, statesmen, philosophers, generals, leaders, and influential [people] in general, when they set their hands to do that which is for the benefit and blessing of their fellow [people]. By it the Lord guides in the affairs of [humanity] and directs the courses of nations and kingdoms. By it the Lord gives ennobling art, the discoveries of science, and music like that sung in the courts above.

With this as a background I would suggest that there are many levels to answer the question as to why diverse images of Christ are important for Christians themselves, and for people learning or teaching about Christianity.

Representation

One reason for their use is the importance of representation. One of my daughters is a Primary school teacher and she was talking about scientists who were in the public eye, and the important work they are doing. She used the example of Dr Margaret Aderin-Pocock. There was slight confusion among some students because she was a black woman, and she therefore did not meet the expected image of a scientist. This was the point, and a black child in the classroom was thrilled to see himself in the example being used. This is the idea behind the No Outsiders initiative that seeks to represent different family types in books that are read in the classroom, and initiatives that seek to include people from diverse backgrounds in the material that is used in all of our classrooms. As a Professor of Religious Education who writes a lot about smaller religions, this reminds me of the development of Rastafari.

Rastafari developed in Jamaica during the 1930s following the coronation of Haile Selassie as Emperor of Ethiopia. One of the first to preach a Rasta ideology was Leonard Howell who taught that Haile Selassie was the Second Coming of Jesus foretold by the Bible. Howell’s message was rooted in Christianity, but was also seen to be anti-colonial in nature drawing on an African ideas and identity, offering an approach different to the European Christianity that was found in Jamaica and surrounding islands. It was a message of black empowerment and a policeman who witnessed Howell’s first declaration of Haile Selassie in 1933 recorded:

The Lion of Judah has broken the chain, and we of the black race are now free. George the Fifth is no more our King … Ras Tafair [sic] is King of Kings and Lord of Lords. The Black people must not look to George the Fifth as their King anymore – Ras Tafair is their king (cited in Murrell, et al, 1998, p. 38).

Howell wanted to formulate a spiritual practice that would give a political voice to Jamaica’s poorest workers. Rastafari is a religion that developed a distinctive racial hermeneutic of history and identity. It sought the reclamation of black identity and the establishment of ‘Black Supremacy’ the place of the downtrodden would be raised. In the ‘colonial’ representation of Christianity those on the margins of society did not seem themselves represented, and as such religion was associated with the oppressor. The black people of the West Indies could not see themselves in the Christianity of the time. The meaningful inclusion and representation of all races enables Christianity to be embracive and meet the needs of all people.

Is God Colour Blind?

Professor Anthony Reddie writes of this type of approach to Christianity that is now being replaced as leaders, clergy and members become aware of the need to be truly diverse. He does so in a way that helps people understand that they may not recognise the power dynamics of the status quo. In his book Is God Colour-Blind?: Insights from Black Theology for Christian Faith and Ministry he describes an activity he leads surrounding the choosing of whether to eat a standard meal or their favourite meal:

In the exercise, food is the metaphor for culture and humanity. Too often, the wider societies in many predominantly White Western countries have neither reflected nor met the cultural and emotional world of Black people. While some have utilized Black cultural practices, such as tapping into their music, popular culture, fashion, art, expression and so on (often for commercial gain), they have not affirmed the peoples themselves. Some people may have chosen to eat the standard meal. If that was their choice and they genuinely do not mind not giving up their favourite and would really prefer to eat the standard meal, then that is fine. But there are many Black people who would genuinely prefer to eat their favourite meal but cannot bring themselves to admit this in public for fear of being identified as being ‘separatist’ or accused of not wanting to ‘integrate’. Often, in White majority Christian-influenced societies, the emphasis is upon ‘integration’ and a ‘colour-blind’ doctrine as a means of handling contentious issues of difference. In the context of the meal-test exercise this involves Black people being persuaded to eat the standard meal; that is, to be less like themselves and to be the same as that which is characterized as the standard or the norm, namely White people (Reddie, 2020).

This highlights to me, that it is possible to be within a system and not recognise the implied norms that exist. In Christianity this may be the representation of Jesus as a white man. This is the norm that Western Christianity has developed over the centuries, and is the accepted representation of him. If I look at the art of Jesus I have in my home, all of it is of this Western representation. This is not wrong, these pieces of art are ways that I connect with the Divine, and they help me understand my relationship with Him. However, one of the things that I need to understand is the privilege I have in being able to say that I don’t see race and that race is unimportant in my worldview. Why? It is because I have never had to consider my race when making decisions or being faced with opposition or representation. Anthony Reddie helped crystallise (though my understanding is still developing) to me the idea that race is an integral part of who we are. We consider that God created all of us as his children in all of our diversity, yet we are then to subsume or, as others suggest, disregard that diversity as we become part of the Christian communion.

This is an important point. We read in Galatians:

So in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise (3:26-29).

When we become disciples of Christ all of our differences are taken away, we become one in Christ. Our most important identity is that of being clothed in Christ. I absolutely agree with this statement, I am a child of God, I am a disciple of Christ. Those are the two most important aspects of my identity. However, it does not mean that the other aspects are unimportant.

One in Christ Jesus

Paul Edwards has suggested that the representation of Christ in diverse ways is anathema to this message of being one on Christ Jesus:

To suggest that we need racially diverse images of Jesus cheapens the reality. The reality is that Jesus, through his humanity and as God in human flesh, died to banish racial, social and class distinctives. In Christ we “…have put on the new man, which is renewed in knowledge after the image of him that created him: here there is neither Greek nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision, Barbarian, Scythian, bond nor free: but Christ is all, and in all” (Colossians 3:10,11). All the nations of men are made “of one blood” (Acts 17:26) and are redeemed by “his own blood” (Hebrews 9:11-15). We don’t need white images of Jesus, black images of Jesus, Chinese images of Jesus, or even Jewish images of Jesus. We need Jesus! (Paul Edwards, 2007).

Surah 49:13 of the Qur’an helps us understand this a little bit more. In describing the diversity of creation, we read:

O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous of you. Indeed, Allah is Knowing and Acquainted.

We have diversity so that we “may know one another”, the diversity is not to segregate or to discriminate. It is at this point that we recognise the importance of Paul’s metaphor as the Church as the body of Christ. Each individual part is different, but each is equally important to the whole:

Just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ. For we were all baptized by one Spirit so as to form one body—whether Jews or Gentiles, slave or free—and we were all given the one Spirit to drink. Even so the body is not made up of one part but of many. Now if the foot should say, “Because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason stop being part of the body. And if the ear should say, “Because I am not an eye, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason stop being part of the body. If the whole body were an eye, where would the sense of hearing be? If the whole body were an ear, where would the sense of smell be? But in fact God has placed the parts in the body, every one of them, just as he wanted them to be. If they were all one part, where would the body be? As it is, there are many parts, but one body. (1 Corinthians 12:12-19)

Recognising all people as members of the body of Christ helps us to celebrate and integrate the Church and kingdom of God. Finding ourselves represented in the Kingdom of God is crucial in understanding our relationship with God. I would suggest that diversity of our art and of our worship is replicating the diversity of God’s creation. We have the responsibility to know one another, not be to threatened by what some would perceive as the ‘other’. We might be challenged to question our attitudes and received norms, and that might be difficult, but there is, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer suggested, a cost to our discipleship.

Challenging our contexts

Returning to the original context of this post- the diverse representations of the Holy Family. We might be challenged by images we are not familiar with, and within which we do not see ourselves. Central to my faith is the idea that Christ is the Saviour of all, regardless of anything that might be used to divide. It is through this lens that I view these pieces of art- recognising that it is through our contextual and cultural lenses that we come to Christ as his disciples.

Indeed, all representations of Christ are also reflections of our contexts. These include the written expressions of faith that we find within the Gospels. Boxall (2020) suggests Luke is a literal artist, but also a metaphorical one in the way that he writes.

The two Gospel writers who included the Nativity story chose events that reflected different perspectives. What is important is that the narratives are not contradictory, rather they chose to include different emphases because of their sources, and also because of who they were writing to. What is really interesting is that as we look at the accounts individually we can actually learn more about who Jesus is and his impact on history, the world and on us as individuals than when we focus solely on the composite and complementary version we are so familiar with.

Matthew and the Nativity

When we read Matthew’s Gospel we read a book that was written for a Jewish audience. Throughout the Gospel, Matthew makes over forty references to what we now call the Old Testament. With this background we are able to look at the way that he relates some of the Nativity story and understand why he chose to emphasise certain events and gloss over, or miss out others. Matthew’s Gospel or ‘Good News’ begins with an outline of Jesus’ genealogy:

The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham (v1)

The first seventeen verses of the Gospel are dedicated to the Saviour’s family tree- there are many that we recognise, but also many that the Jews of the time would similarly have connection with. Probably the ones that would stand out the most would be Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, as well as Jesse, David and Solomon. If we look at this second group there are many scriptures of the promised Messiah that suggest a Davidic line:

And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots:… (Isaiah 11:1)

The stem of Jesse, or the descendant of Jesse spoken of is the Saviour shown in the writings of Jeremiah:

Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will raise unto David a righteous Branch, and a King shall reign and prosper, and shall execute judgment and justice in the earth. In his days Judah shall be saved, and Israel shall dwell safely: and this is his name whereby he shall be called, THE LORD OUR RIGHTEOUSNESS 23:5-6).

Although Luke does mention a genealogy to David it is linked with chapter 3 and is not the first thing that he declares. In so doing, Matthew is establishing the Saviour as the fulfilment of the prophets, he does something similar later in his Gospel in Matthew 5 where in the Sermon on the Mount, the Saviour is seen to be the fulfilment of the Law. I have only focussed on the ‘big’ names in the genealogy but there are others who would be immediately recognisable to the Jewish audience such as Thamar (v3) who has a very interesting story (1 Chronicles 2) that may help people reflect on the idea that it is not one’s background that is so important.

Matthew’s retelling of the Nativity story is also slightly jarring for the narrative that we are used to, because the focus of Matthew’s narrative is the voice of men. The first verses following the genealogy are these:

Now the birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise: When as his mother Mary was espoused to Joseph, before they came together, she was found with child of the Holy Ghost. Then Joseph her husband, being a just man, and not willing to make her a publick example, was minded to put her away privily. But while he thought on these things, behold, the angel of the Lord appeared unto him in a dream, saying, Joseph, thou son of David, fear not to take unto thee Mary thy wife: for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost. And she shall bring forth a son, and thou shalt call his name JESUS: for he shall save his people from their sins (Matthew 1:18-21).

This highlights the role of Joseph, the annunciation to Mary seems to have been skipped over. It is not that Mary is unimportant, for in the next couple of verses Matthew quotes Isaiah in recognising ‘a virgin shall be with child, and shall bring forth a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel’ (v22). It’s that for Matthew and his audience the importance of the powerful male voice is central to the narrative. This is, perhaps, emphasised when the next people that we hear of are the wise men and Herod:

Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judæa in the days of Herod the king, behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem (Matthew 2:1).

Why we might not find the wise men in Luke will be discussed later, but for Matthew, Jesus’ birth was a mighty event and while it centred around the powerful in society, it also turned those expectations on their head. The wise men visited Herod to find the new king, but he was not to be found there. But in fulfilment of prophecy he was to be found:

In Bethlehem of Judæa: for thus it is written by the prophet, And thou Bethlehem, in the land of Juda, art not the least among the princes of Juda: for out of thee shall come a Governor, that shall rule my people Israel (Matthew 2:5-6).

The gifts which the wise men presented him were befitting one of the lineage of David who would be the anointed one, the Messiah.

And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshipped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense, and myrrh (Matthew 2:11).

Each of these gifts had symbolism attached that would be immediately known to the reader. Gold was a symbol of Kingship and Frankincense as a symbol of the divine as it was often used in a priestly role (see Leviticus 24:7 and Psalm 141:2). It is interesting to me that the Saviour is referred to as ‘Prophet, Priest and King’ (see Hymn 136)- in the Old Testament these roles are usually separate, but they find their fulfilment and come together in the person of the Saviour- He is our Prophet, Priest and King. Matthew establishes this in the first two chapters through the scriptures he uses, and the emphasis that he places in the gifts.

I haven’t mentioned so far the gift of myrrh, as this is a slightly strange gift to bring a child. It was often used in the anointing of the dead. In this gift, the wise men are foreshadowing a day when the Saviour would die. Essentially helping us to understand that the main purposes of the Saviour’s life was to die for us. Even at this early stage of his life, his life and mission were clear to those that understood. The wise men understood this, and so would have the readers of Matthew.

The Saviour’s birth in Matthew is noticed and includes the rich and powerful of the world. The conclusion to the story highlights again Matthew’s emphasis on the Saviour being a fulfilment of the Old Testament, and in particular Moses. The massacre of innocents by Herod when he discovers the wise men have returned home without reporting to him, would be reminiscent to the Jewish reader of a similar event around the time of the birth of Moses. Like Moses, the Saviour escapes- this time not in a basket, but with Joseph and Mary with Joseph having been warned in a dream to go to Egypt. Thus the reader of Matthew can understand very clearly that the birth of Jesus is the fulfilment of Old Testament prophecy, that he is the Messiah and he is of infinite worth so that even the rich and powerful seek him.

Luke and the Nativity

As we read Luke’s account of the Nativity it is important to note that he was writing for a Roman audience and also addressed the Greek world. Although we don’t find the genealogy of Jesus until chapter 3 when the events of the Nativity are over, the genealogy that Luke uses is specifically influenced by his audience. Like Matthew he includes the Patriarchs through the line of David:

Which was the son of Jacob, which was the son of Isaac, which was the son of Abraham, which was the son of Thara, which was the son of Nachor,

But he goes further:

Which was the son of Enos, which was the son of Seth, which was the son of Adam, which was the son of God.

In this genealogy Luke wanted to emphasise more than Jesus as the Messiah for the Jews, but taking it back to Adam and from there to God, Luke was extending the message to all of the human family, including the Gentiles. This is important for us, as the message and the atonement of our Saviour Jesus Christ should be shared with all, and is not limited in its scope and reach.

Luke begins his account of the Nativity with the story of Elisabeth and her husband Zacharias. In discussing this with a friend recently, he pointed out that in distinction to the male dominated narrative of Matthew, one of the first events in Luke is the closing of the mouth of Zacharias, the man:

And when he came out, he could not speak unto them: and they perceived that he had seen a vision in the temple: for he beckoned unto them, and remained speechless (Luke 1:23).

Although there is evidence that Luke may have known of Matthew’s Gospel, I’m not sure this was a direct contradiction but it is interesting to note. The remainder of the story very much focuses on Mary. You’ll remember in Matthew that it was Joseph who he recorded hearing the message from the Angel in a dream. In Luke, he includes the events of the annunciation to Mary:

And in the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent from God unto a city of Galilee, named Nazareth, To a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin’s name was Mary. And the angel came in unto her, and said, Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women. And when she saw him, she was troubled at his saying, and cast in her mind what manner of salutation this should be. And the angel said unto her, Fear not, Mary: for thou hast found favour with God. And, behold, thou shalt conceive in thy womb, and bring forth a son, and shalt call his name JESUS (Luke 1:26-31).

There is some suggestion that Mary may have been a source for Luke’s writings and this would go some way to explain the detailed narrative that Luke chooses to include. It is also fairly indicative of other aspects of Luke’s Gospel. Throughout Luke there are examples of the author including the stories of those on the periphery of society. Those who may not always have a voice. It begins in the Nativity with a focus on the role of women, but also extends throughout his Gospel. Unique to Luke are the stories of social outcasts (7:37-50, esp. v. 39); The Good Samaritan (10:25-37); Lazarus, a deserted beggar (16:19-31) and Lepers (17:11-19). The Greeks and the Romans spread their culture and language all over the world with the intent of bettering the lives of people. Luke’s message of Christ would appeal to their mind.

There are further examples of this within the Nativity story. Luke is the author who includes the detail that Mary:

…she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger; because there was no room for them in the inn (2:7).

There could be no more humble beginning for the Saviour of the world. After Mary, Joseph and John the Baptist, the first witnesses to the identity of Jesus as the Son of God were similarly lowly:

And there were in the same country shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them: and they were sore afraid. And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you; Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying, Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men (Luke 2:8-14).

That the Saviour would become the Good Shepherd was perhaps one reason why the shepherds were visited by the angels. It is important to note that the shepherds, while great examples were of a low station. This helps us understand the message wasn’t just for the rich and the powerful, but also for the poor and lowly. Jesus Christ came into the world to save all people, and Luke emphasises this in reciting this part of the story. Whereas for Matthew, this part might have been a stumbling block to his Jewish audience. As an aside it is interesting to note that the biblical scholar Alfred Edersheim and the apostle, Bruce R. McConkie have suggested that these shepherds may have been those who were tasked with tending the lambs destined for use in the Temple, those lambs who were without blemish sacrificed at Passover. If this is so, then the story also serves to foreshadow the Saviour’s role as the Lamb of God, without blemish that was to be sacrificed for the sins and pains of the world.

Of further interest is the use of the word ‘found’ when it describes the shepherds visit to the Saviour. This suggest that they had to look. One commentator has noted how difficult it is to find a house in a town with no addresses/street names. Maybe this helps us understand that we need to put effort in to find the Saviour in our lives.

Why are there no wise men in Luke’s account- it could be that their visitation could have appeared to have been a threat to Roman rule and so Luke chose to omit their visit to focus on the message he wanted to share with the Romans with no distractions.

The final people in Luke’s account who have a part to play were two faithful people: Simeon and Anna. They had waited to witness the Messiah, and when Jesus was taken to the Temple at the age of eight days and was there recognised as the anointed one. Simeon took the Saviour:

up in his arms, and blessed God, and said, Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word: For mine eyes have seen thy salvation, Which thou hast prepared before the face of all people; A light to lighten the Gentiles, and the glory of thy people Israel (Luke 2:28-32)

Anna herself was at least 84 years and of the tribe of Asher. Those two facts were enough to place her on the periphery of society, Edersheim has noted of Anna:

To her widowed heart the great hope of Israel appeared not so much, as to Simeon, in the light of ‘consolation,’ as rather in that of ‘redemption.’ The seemingly hopeless exile of her own tribe, the political state of Judæa, the condition – social, moral, and religious – of her own Jerusalem: all kindled in her, as in those who were like-minded, deep, earnest longing for the time of promised ‘redemption (The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah, p. 140).

Luke’s telling of the story expands significantly the scope of the impact of the birth of the Saviour. Knowing he intricacies of both accounts helps us understand the impact that the Saviour had on the lives of Matthew and Luke, the impact it had for their audiences, but far more it helps us understand the impact that the birth, life, death and resurrection of the Saviour can have on us today.

Understanding the context of these first writers helps us understand why they chose to emphasise different parts of the nativity, and not include others.

The context of art

Although further removed in time, this is exactly what artists who depict the nativity are doing, and also help us understand the questions we should be asking. In a painting entitled “Adoration of the Shepherds” by Domenico Ghirlandaio we notice elements that are purposeful inclusions by the artist, that highlight the links between the birth of the Saviour and his death. I noted earlier that Matthew chose to include the myrrh for this purpose. In Ghirlandaio’s work “there stands in between the child and the ox and donkey, not a manger or feeding trough, but a stone sarcophagus, albeit filled with hay, Worshippers contemplating Ghirlandaio’s altarpiece at Mass would be presented in this depiction of Christ’s birth with a stark anticipation of his death” (Boxall, 2009, 24). I use this ‘traditional’ image as it depicts Mary and other sin clothing that would not be out of place in the 15th Century, as well as a sarcophagus that fulfils the artist’s purpose, this is without mentioning the shepherds and the lamb representing the lamb of God who would be slain for the sins of the world.

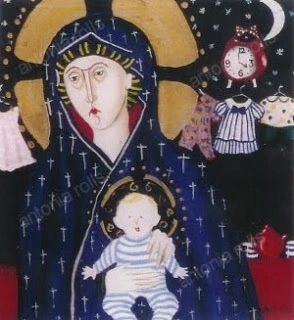

This type of foreshadowing and emphasis is also evident in Antonia Rolls “4am Madonna” which shows Mary’s cloak adorned with crosses.

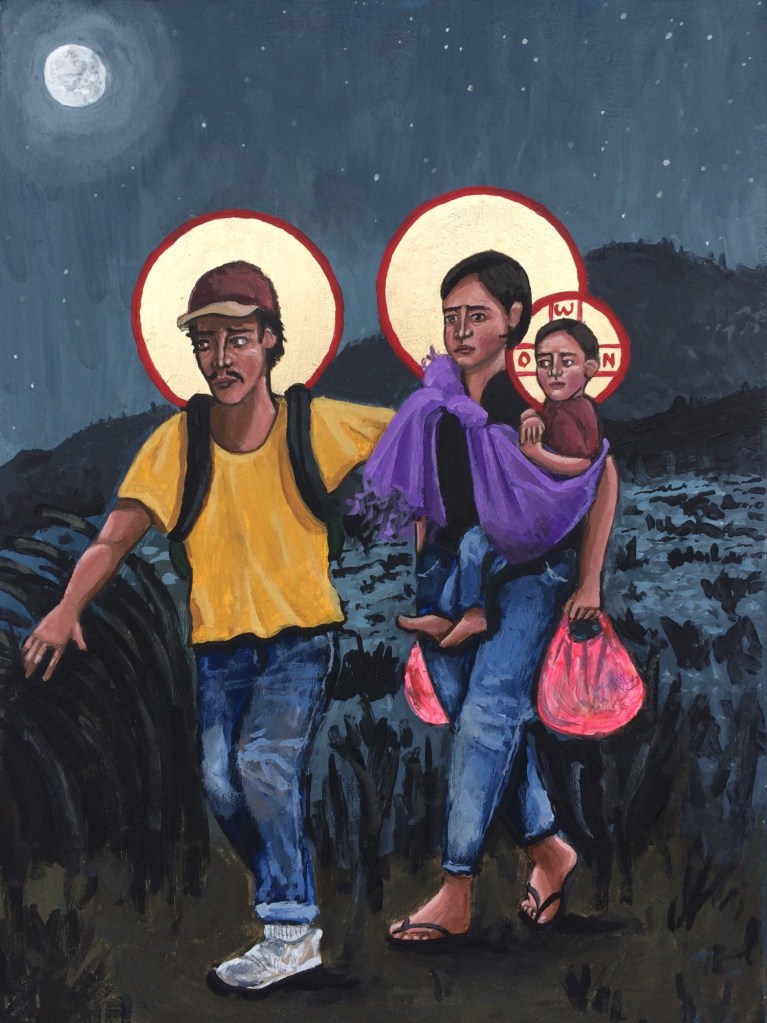

Each of the pieces of art tell us about the events of the nativity and also about the faith and context of the artist. Sometimes this is challenging. Consider Kelly Latimore’s “La Sagrada Familia” which depicts the Flight into Egypt of the Holy Family as modern day refugees.

Latimore describes her motivation for the painting:

I painted ” La Sagrada Familia” the day after the 2016 Election. It was mainly inspired by a trip with my partner Evie and encountering some undocumented immigrants. We were sitting around a bonfire one night with this young man from Guatemala who told us why he was in the United States, his struggles, his hopes, and fears. He had come here as a teenager, only to be deported and then almost beaten to death in Mexico. He eventually crossed the desert again to the United States. Everything about him broke us. He has the image of God within him. As we were hearing all of the hateful rhetoric that was anti-immigrant, anti-stranger, his experience immediately came to mind while creating this modern holy family image and how the refugee Jesus, Mary, and Joseph must have felt fleeing from Herod 2,000 years ago.

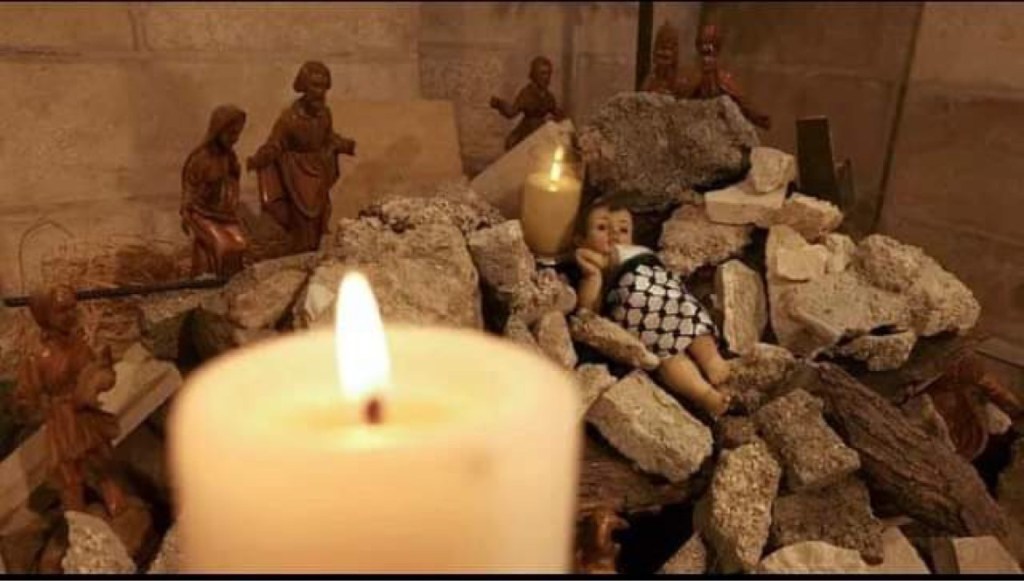

One other image I shared was of “Jesus in the rubble”, which was a doll of the Christ child in rubble in the Lutheran Church in Bethlehem. “If Christ were to be born today,” Reverend Munther Isaac, the church’s minister explained, “he would be born under the rubble… this is a powerful message we send to the world celebrating the holidays.” As much as the artist’s motivations are important, so too, as with all art is my response as a viewer or consumer of art. This led me to consider the need for peace on earth, but as the Saviour promised:

Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid (John 14:27).

For me, Christ’s peace is different as it is more than an absence of conflict, rather, it is the filling of the world with love. That is perhaps why I share the various images of the nativity, it is as much in the eye of the beholder as much as it is in the eye of the painter. We learn a lot about ourselves in our response with art. A lot of my work is within the religious sphere and I spend a lot of time working in inter-faith. Within this arena I posit the existence of a dialogical space between religions that constitutes “holy ground”. This third space enables a place where adherents of two religions meet to transform their understanding of one another, but also their understanding of themselves and their faith. Engagement with a third space as a place of “radical openness” (McMaster, 1999: 28) provides a perfect description of the type of space needed for inter-faith dialogue to be successful.

A dialogical third space

My research as explained focussed around the possibility of religious people learning from other people’s religious experiences. As an example that I could learn deeper things about my own faith as I engaged with people who held similar beliefs, both in the sense of defence, but also in understanding how others interpreted certain obligations or beliefs meant I could gain a greater appreciation of them in my own context. As this study was concluding, I was invited to give a paper about Tolkien’s religious beliefs in his creation myth (an updating of my previous work). Working on the two projects simultaneously helped me realise that the strengthening and deepening of faith I experienced in dialogue with other religions could be replicated in my relationship with Middle Earth. I would suggest that this dialogue could also be engaged in with a reading of Tolkien’s work, and other writings. The finding of virtues will come in the encounter between individuals and the world of middle earth. In genuine encounters with art people can develop strength and faith as they are open to learn from each other. Gideon Burton has expressed a similar view when experiencing Mozart: “At the same time, this reflection reveals something back to Latter-day Saints about who they are and how their culture responds to great art: we read The Magic Flute, and The Magic Flute reads us” (2004: 23). We cannot help be changed by engagement with truths and art. The benefits of engagement with truths are not just a greater understanding of others, but also a greater understanding of what it means to be me.

Thus, if there exists a third space in inter-faith dialogue, it could also exist when we engage in dialogue with a story- when the text itself becomes our dialogue partner. When we read or hear a story we cannot help but view it through the spectacles of our own experience. Essentially this could be seen to be a prism- where the reader is the prism with all of their life experiences which make sense of the story they are hearing. Orson Scott Card (a science fiction writer) has called this an “epick” approach to criticism where a person or group finds relevance for themselves in a particular story or, in this context, piece of art.

Final thoughts

Also interesting is the reality that we all respond in different ways. I outlined that I was inspired by ‘Jesus in the rubble”, I have a friend who ‘hated’ it as it was politicising one of the most sacred events in our faith. That discussion helped me explore why I, contrary to my friend, consider Christ to be a political figure. A figure whose call to follow him, means that my discipleship influences every aspect of my life. My desire for social justice is because of y discipleship rather than in spite of it. That is the beauty of art, it can create discussion and help us understand who we are, and especially who we are in relation to God and to others.

This was envisaged to be a short post about the importance of using a diverse range of images of Christ. It’s taken me in many different directions. At the end of everything there are many reasons why the use of diverse images is important. The art we see may be challenging to us and where we are, but it is transformational as we find ourselves and others in the images we use, and the Kingdom of God of which we are a part. Art is media that enables God to come to us where we are.

Do you have a list of titles and artists of this art? It’s beautiful.

LikeLike

Hi- not together I’m afraid but if you head over to my instagram @jamesdholt and go back to last December (2023) each post gives credit to the artist- I don’t post a tonne so there’s not far to scroll. Sorry- one day I might get to captioning them here.

LikeLike